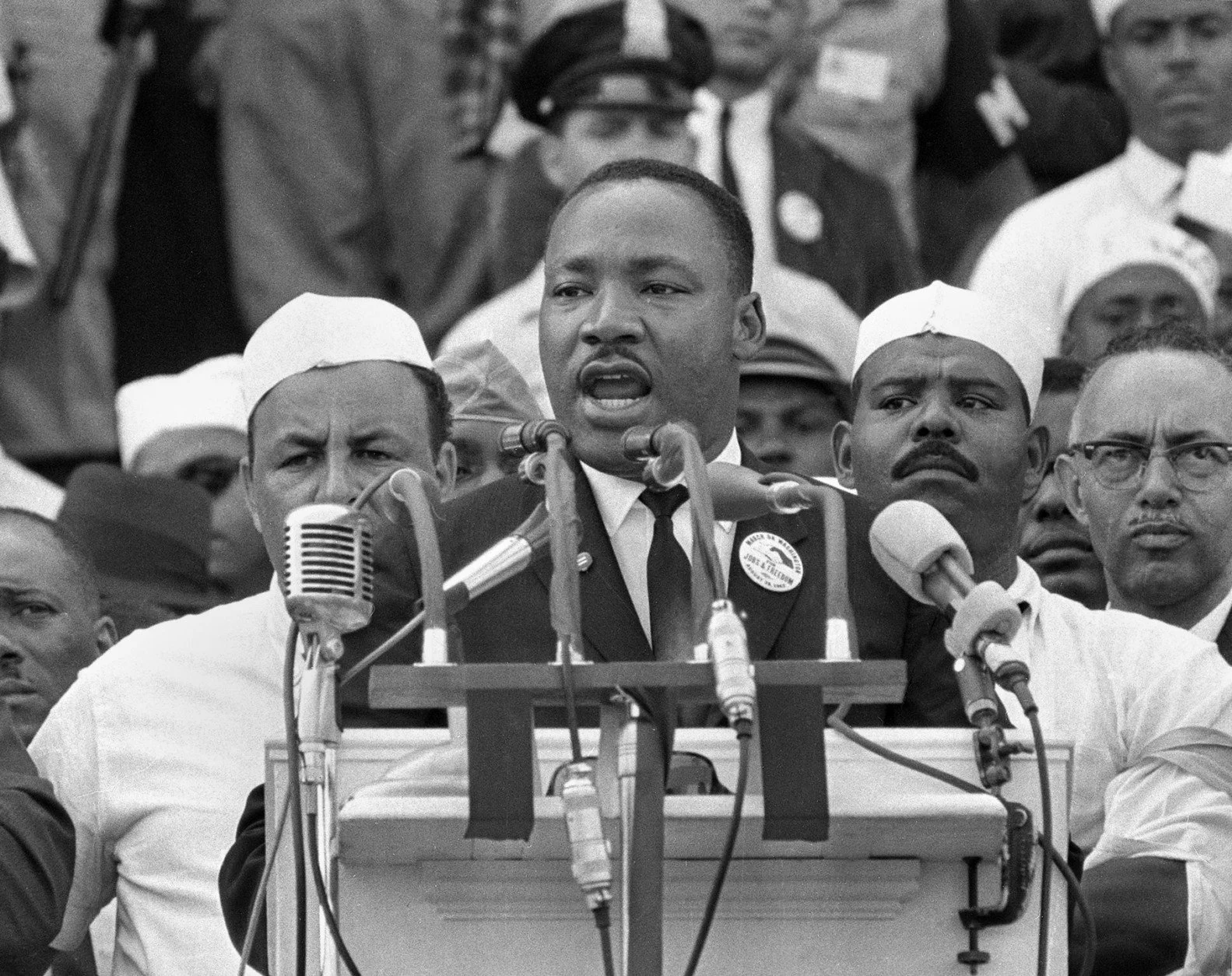

MLK.Jr : I Have A Dream

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. Five score years ago a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree is a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But 100 years later the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later the life of the Negro is still badly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. So we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. . . . We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. . . . The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. . . . We cannot walk alone. And as we walk we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their adulthood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream. . . . I say to you today, my friends, though, even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream . . . I have a dream that one day in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today . . . This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning. “My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountain side, let freedom ring.” And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that. Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi, from every mountain side. Let freedom ring . . . When we allow freedom to ring—when we let it ring from every city and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last, Free at last, Great God a-mighty, We are free at last.”

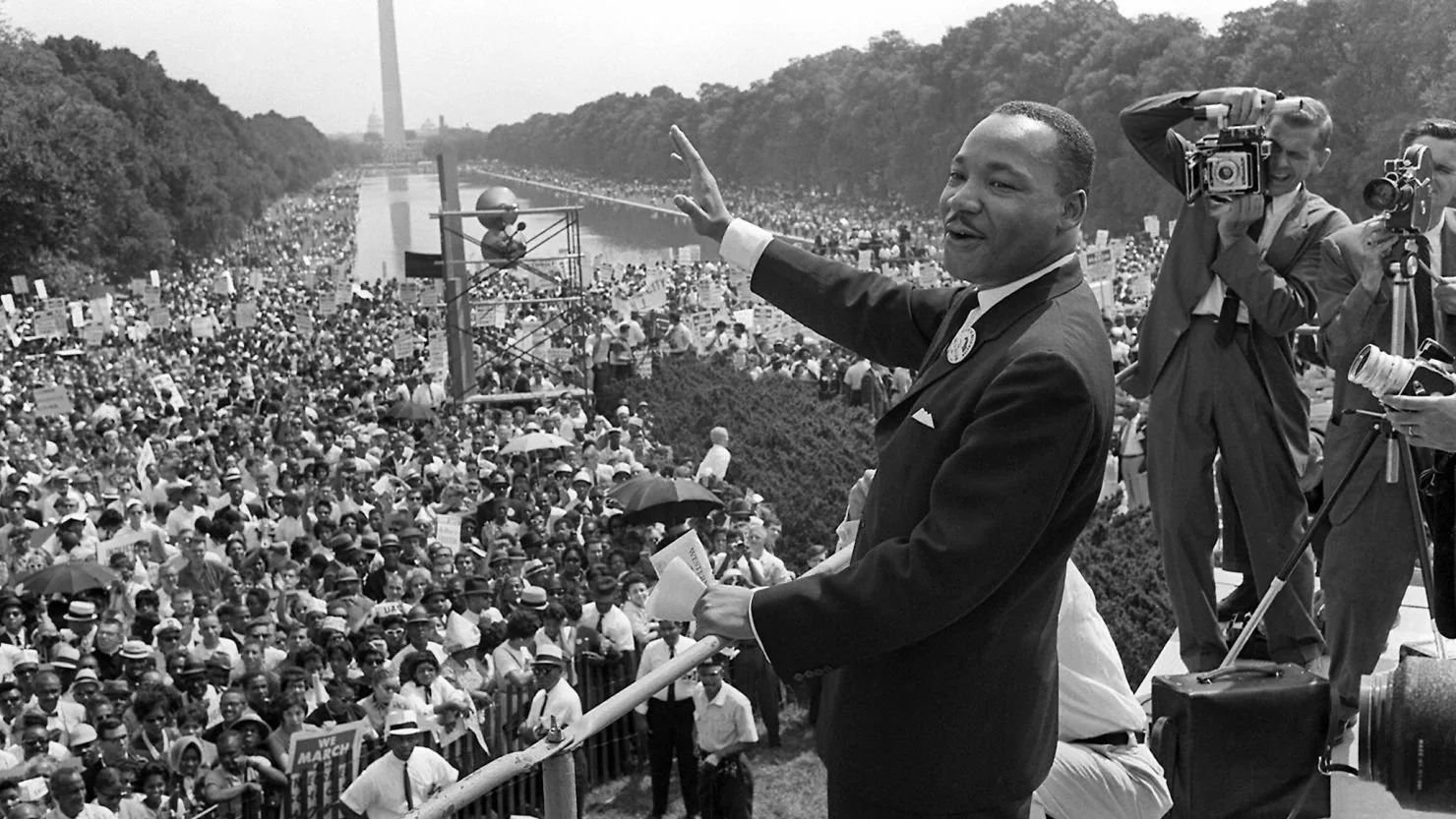

The crowd erupted in a thunderous ovation, a wave of sound that rolled across the National Mall like the very "mighty stream" of justice Dr. King had just envisioned. Hands clapped, some rose to their feet, and others wept, the afternoon sun glinting off the tears of those who had carried the weight of centuries into that moment. On the stage, Dr. King stood motionless for a heartbeat, his eyes closed as if savoring the echo of his own dream. Then, with a slight bow and a nod to Mahalia Jackson, who had opened the march with "How I Got Over," he stepped back, the applause trailing into a hush that settled like a vow over the 250,000 souls gathered.

But the work was far from done.

October 1964, Selma, Alabama

The dust of Magnolia Street had not yet settled from the day’s voter registration drive when Sarah Thompson remembered Dr. King’s words: Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. Now, she stood in Selma, her hands calloused from distributing pamphlets and her spirit hardened by arrests. The Civil Rights Act had passed, yes—but here, in this town where sheriff’s deputies still wielded batons like scepters, equality felt as distant as the stars.

That night, in a dimly lit church, Sarah joined a circle of activists. A young man named John Lewis, his face still bruised from the march a week prior, spoke of the need for another protest across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. “We will not be stopped,” he said, “not by tear gas, not by lies.” Sarah’s heart pounded. She thought of her mother’s voice, warning of the dangers of “uppityness,” and her father’s silent labor in a segregated factory. Yet Dr. King’s dream had given her a louder voice.

March 1965, The Bridge

The photographers captured it all—the sea of demonstrators in cotton dresses and Sunday best, the determined glint in their eyes. Sarah held the hand of a teenage boy, no older than her own son back home, as they faced the line of waiting troopers. We cannot walk alone, Dr. King had said. But today, they walked together, a river of humanity surging against the walls of hatred.

When the first boots hit the bridge, Sarah braced herself, but no violence came. Instead, the troopers raised their hands—a silent surrender, the power of nonviolence having shifted the tides. On the other side, a journalist scribbled notes, later reporting, “The bridge trembled not with force, but with freedom.”

August 1965, Washington D.C.

The Voting Rights Act’s passage was signed, but the celebration was bittersweet. Sarah stood outside the Capitol, watching a group of Black children trace their fingers over the Statue of Freedom atop the dome. “Will it be enough?” she whispered to a friend.

“Dreams are just the beginning,” her friend replied. “Now we build.”

Years later, as she cast her first ballot in a poll where no white official sneered at her ID, Sarah thought back to 1963. Dr. King’s dream had not vanished into the wind; it had taken root in the cracks of a broken system, growing through the soil of struggle. And though new battles emerged—over housing, over justice, over the meaning of equality—the words still rang clear in her heart:

“Free at last, free at last, Great God a-mighty, we are free at last.”

But freedom, she knew, was not a finish line. It was a bridge, ever-crossing.

Now take a minute of silence!

Imagine, for a moment, that the crack of gunfire that silenced Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, was never heard.

Imagine that he stepped down from the balcony of the Lorraine Motel not in death, but in peace and his life preserved, his voice undimmed.

What would our world look like today if Martin Luther King Jr. had lived?

We might have seen him walk hand-in-hand with Coretta Scott King into the new millennium, his silver hair a crown of enduring wisdom, his sermons echoing not just in churches but in classrooms, boardrooms, and global peace summits.

Instead of being memorialized too soon, he would have evolved—grown, adapted, challenged—a living conscience in a restless world.

The 1970s, a turbulent decade of economic upheaval and political disillusionment, might have found its moral compass in King.

While Watergate eroded trust in government, King could have led a national campaign for ethical governance.

His philosophy of nonviolent resistance might have extended beyond civil rights to environmental justice, calling for a "Poor People’s Campaign" that included access to clean air, water, and sustainable communities.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” he wrote in the Birmingham jail words that could have inspired coalitions against pollution in urban neighborhoods and indigenous lands alike.

By the 1980s, as the crack epidemic ravaged inner cities and Reaganomics widened the wealth gap, King might have emerged as the most potent advocate for economic equity.

He could have stood at the National Mall once again, not just demanding civil rights, but a radical reimagining of opportunity.

Perhaps he would have launched a second Poor People’s Campaign, uniting struggling communities across racial lines white Appalachians, Black urbanites, Latino farmworkers, Native tribes was all bound by shared hardship.

His call would not be for handouts, but for systemic fairness, for dignity in labor, for the right to thrive.

And what of the 1990s?

As the world celebrated the end of apartheid in South Africa, King could have partnered with Nelson Mandela, becoming a global emissary for peace and reconciliation.

Imagine him mediating conflicts not with airstrikes, but with seminars of bringing warring factions to the table over shared meals and Scripture.

No military intervention in the Balkans, perhaps, but a King-led truth and healing process.

A Nobel Peace Prize nominee not once, but several times for brokering dialogue in Northern Ireland, for advocating for Soviet dissidents, for pioneering interfaith dialogue between Muslims, Jews, and Christians.

In the age of the internet, King might have become a digital prophet—posting sermons on social media, hosting livestream town halls, educating a generation raised on soundbites about the long arc of justice.

He would have challenged Silicon Valley not just to connect people, but to uplift them. He might have warned against the commodification of attention, the amplification of hate, the erosion of truth.

“Technology,” he could have said, “is a tool; love is the engine.”

On September 11, 2001, when fear cracked open the American soul, King’s voice would have been a balm.

While others called for war, he would have called for understanding.

“We cannot drive out hatred with more hatred,” he might have reminded the nation.

“We must respond to terror not with terror, but with truth, with empathy, with justice.”

His influence could have shifted U.S. foreign policy toward diplomacy and humanitarian investment, preventing the long, costly wars that followed.

In 2020, amid a pandemic and mass protests against police brutality, King would not have been a statue in Washington, but a living elder guiding the movement.

He might have stood alongside the mothers of Trayvon, George, and Breonna not just in solidarity, but in strategy.

His dream would have grown broader, embracing LGBTQ+ rights, disability justice, climate refugees—anyone cast aside by the margins of society.

Politically, his presence might have reshaped the Democratic Party, pulling it steadily toward moral courage over electoral pragmatism.

A King-backed candidate in 2008 might have made Barack Obama’s path smoother, or perhaps King himself would have urged Obama to go further bolder on healthcare, stronger on prison reform.

And by 2024?

We might live in a nation where reparations are not just debated but implemented in meaningful ways, where schools teach not only King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, but his critiques of militarism and capitalism. We might have a culture less obsessed with division and more committed to the “beloved community”—a term he cherished.

Of course, this is imagination.

We cannot know for certain how history would have bent with his continued presence. But we do know this: the world without Martin Luther King was dimmer, louder with conflict, slower to heal.

Yet perhaps he lives still and not in the past tense, but in every person who chooses love over fear, action over apathy, justice over comfort.

The dream was never his alone.

It becomes real not in the world that might have been, but in the world we choose to build today.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s the most powerful legacy of all.